Privatezen This is a blog post by thisisaaronland that was published on Feb 02, 2018 and tagged electron, mapzen, privacy, privatesquare, sqlite, venues and whosonfirst

Way back in 2012 I started working on a project called Privatesquare. At the time I was doing a lot of work around the idea of personal archiving and Privatesquare was originally conceived as a simple backup of my Foursquare check-ins.

At one point I started thinking: I don’t care if Foursquare knows I went to the bar around the corner, but maybe I’m not so keen on them knowing I went to the drug store. At the same time maybe I am interested in having a record of that. So what began as a simple unidirectional archiving project morphed in to a tool where I would check-in to Privatesquare first and then optionally tell Foursquare.

Fun fact: Without Privatesquare the IDs in Who’s On First might have been completely different but that is an entirely other story, for another day.

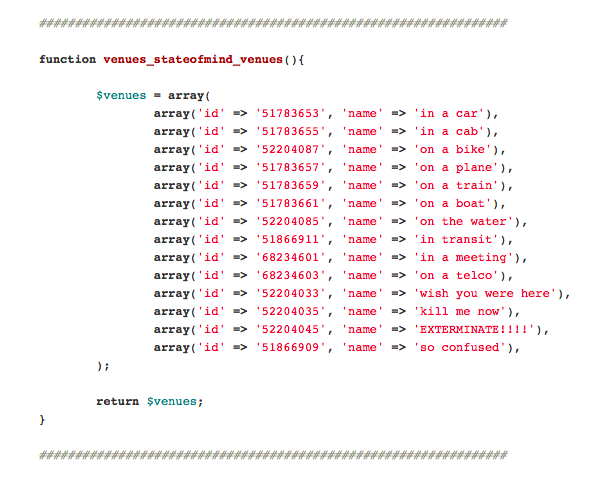

Privatesquare eventually grew more sophisicated allowing you to “check-in” to places not defined in Foursquare. For example, old buildings in New York City courtesy the New York Public Library and so-called “states of mind”. It also added the ability to record travel and to record things you liked or didn’t like in the Atlas of Desire.

Privatesquare was always a mornings-and-weekends project and used a variety of external services to get thing done: Foursquare for venues and search; Stamen for map tiles; The Flickr API for geocoding cities.

The first week I started at Mapzen, in 2015, I remembering thinking: I wonder if I can swap out each one of third-party services used by Privatesquare with an equivalent Mapzen service? The answer, at the time, was “No”.

It was a useful reminder of the work we had set out for ourselves.

Fast forward to the spring of 2017 and I had begun to experiment with small bespoke Electron-based applications, specifically a tool that a person could use to explore and test the Who’s On First API. Electron applications are written in HTML and CSS and Javascript and then bundled up and compiled in to a binary application.

I continue to be interested in Electron apps because they afford the ability to more easily craft something that looks and feels like a native application, across different platforms, without a lot of the boring grunt-work that comes with writing native applications.

After I finished the Who’s On First API Explorer application I remember thinking back to 2015 and wondering if I could finally swap out all of the third-party services in Privatesqure with an equivalent Mapzen service.

The answer this time was “Yeah, probably…”

Instead of updating the Privatesquare web application I decided to build a dedicated Electron application from scratch. I did this for a few reasons:

I didn’t want the extra hassle of running another server with user accounts.

I also didn’t want to store any user data on a remote server.

I wanted to see whether the model that Firefox team had developed for their Sync product could be applied to check-ins and personal location tracking.

I wanted to think about building an application that could be developed and deployed across a number of platforms and devices, each of which might have a purpose-built UI but all of which shared the same underlying data model, in this case a simple SQLite database.

Everything in Privatesquare is private to an individual. There is no way to “share” a place or a list or really anything you do in the application. That is by design but even though you could run your own copy of Privatesquare (and a few people did) if you used my instance then your data was stored alonside everyone’s else data in a shared database that someone else (me) controlled. So it is “private” in as much as you trust me.

That’s a truism bordering on a platitude but in 2018 trust in systems, if not individuals, increasingly seems like it is in short supply. Every day bring news of some previously unknown existential flaw in the fundamental principles of computers and computer networks – aka “the cloud” – so that even if you implicitly trust an operator or a service the guarantee of that trust feels like it is called in to question.

So what does it mean to not store sensitive data (whether it is sensitive or just feels sensitive amounts to the same thing) on a remote server? The problem of course is that people now have multiple computers, big and small, and have come to expect that all those “devices” can and will can in sync with one another.

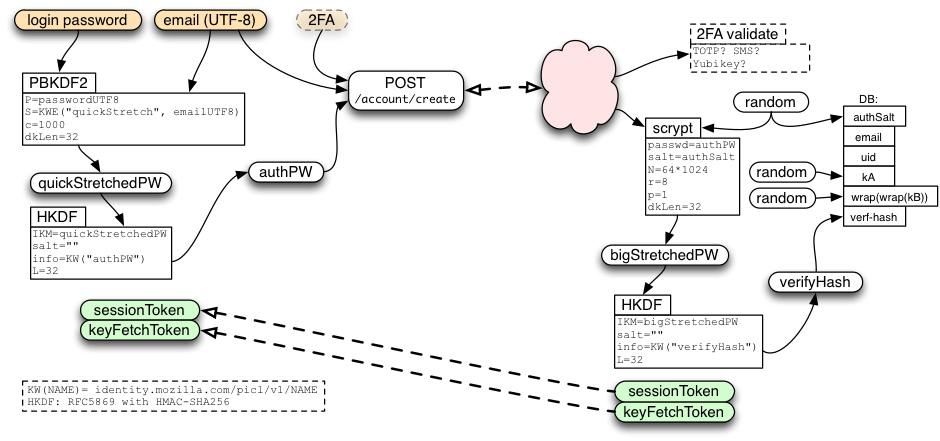

One approach to mitigating this problem is simply encrypting the data in transit, and at rest, between devices. This is how Firefox synchronizes things like browser preferences and bookmarks between a user’s desktop computer and their mobile phone.

Ultimately there is still a server brokering the communication between devices and there is a lot of math and cryptography and there are still user accounts and a bunch of ways you can shoot yourself in the foot and never be able to decrypt your data (that’s what’s going on in the scary screenshot above) but the thing you get in return for all that hoop-jumping is that Mozilla, the parent company of Firefox, doesn’t know what you’re bookmarking.

I don’t belive what Firefox is doing is a perfect solution, by any means, but it feels like forward motion and is at least “better than yesterday”. In as much as “check-ins” are just “bookmarks” by another name, maybe there’s something to learn from people already working on this problem.

It’s also worth a quick tangent to mention differential privacy and Google’s federated learning here.

When user data is encrypted at the service provider level it is problematic for companies that rely on aggregating that data (and hence be unencrypted) in to something they can resell, whether its advertising or genuinely useful secondary services. Nevermind the former but I choose to believe there’s an argument to be made in favour of the latter.

What I think is valuable about projects like differential privacy and federated learning is the idea there might be a way to say to people: We care intensively about whatever it is you’re “doing” but we don’t actually care about you, personally or individually. This is interesting to me for projects like Who’s On First and Privatesquare/zen when it comes to things like validating data but more generally I think there is a need and real value for people to have a way to participate in collaborative efforts with some measure of ambiguity, if not anonimity.

Simson Garfinkel’s presentation on Modernizing the Disclosure Avoidance System for the 2020 Census for the Census Scientific Advisory Committee (CSAC), last year, is a good discussion of some of the benefits and trade-offs in this approach.

Lots of people have written about and demonstrated the value of SQLite databases, none more eloquantly than Paul Ford. Similarly Simon’s Willison’s Datasette project is a good example of how SQLite databases can make “simple things and hard things possible”.

Even before that, though, SQLite has been used under the hood for years by a wide array of applications and services. SQLite databases and small and portable and self-contained (a single file on disk that you could send to someone as an email attachment) and while they still require a user to install dedicated software to work with the data those tools are readily available in 2018.

And lots of different tools can read and write SQLite databases. Aside from the mechanical considerations for using SQLite (only one file to encrypt and decrypt and send across the wire) I like the fact that the raw data that makes the application unique and useful to an individual is something which is also accessible to browse, manipulate or do whatever someone wants with outside of that application.

It provides a useful check and a separation of concerns that forces an application to succeed on its own merits and not because it has the key to all your data.

One day, after showing some work-in-progress of my new Mapzen-enabled Privatesquare – aka “Privatezen” – at the office a colleague asked if this was an official Mapzen project. It was not and never was. I would have enjoyed making it one but we already had million other things on the go so it was a thing that I would poke at in 45-minute increments over coffee in the morning before going to do the “real work” of Who’s On First.

It was and has remained, for now, a tool uniquely tailored to me because I assume I am the only one who can see past all the short-cuts and gotchas to bother using the thing.

It (bookmarking places or “check-ins” or whatever you want to call it) is a thing I’ve always missed since I stopped running a hosted version of Privatesquare. At the same time, I’ve always felt that there was no point in doing Who’s On First unless you could actually do something with the data so this project was a good way to kick the tires.

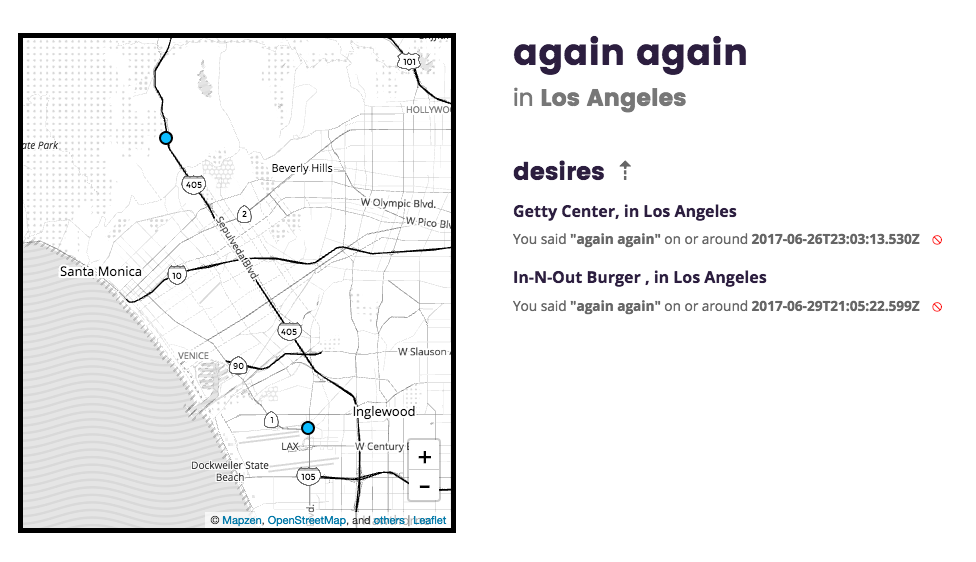

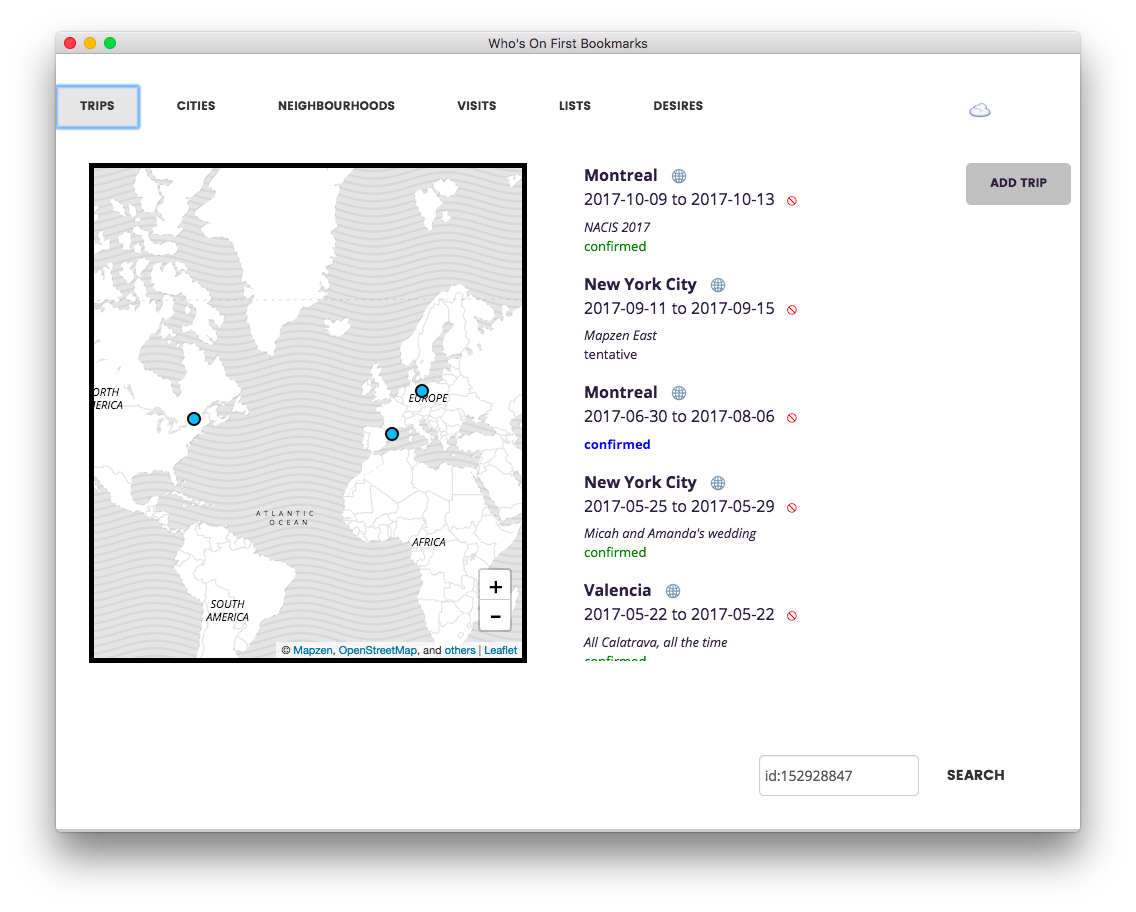

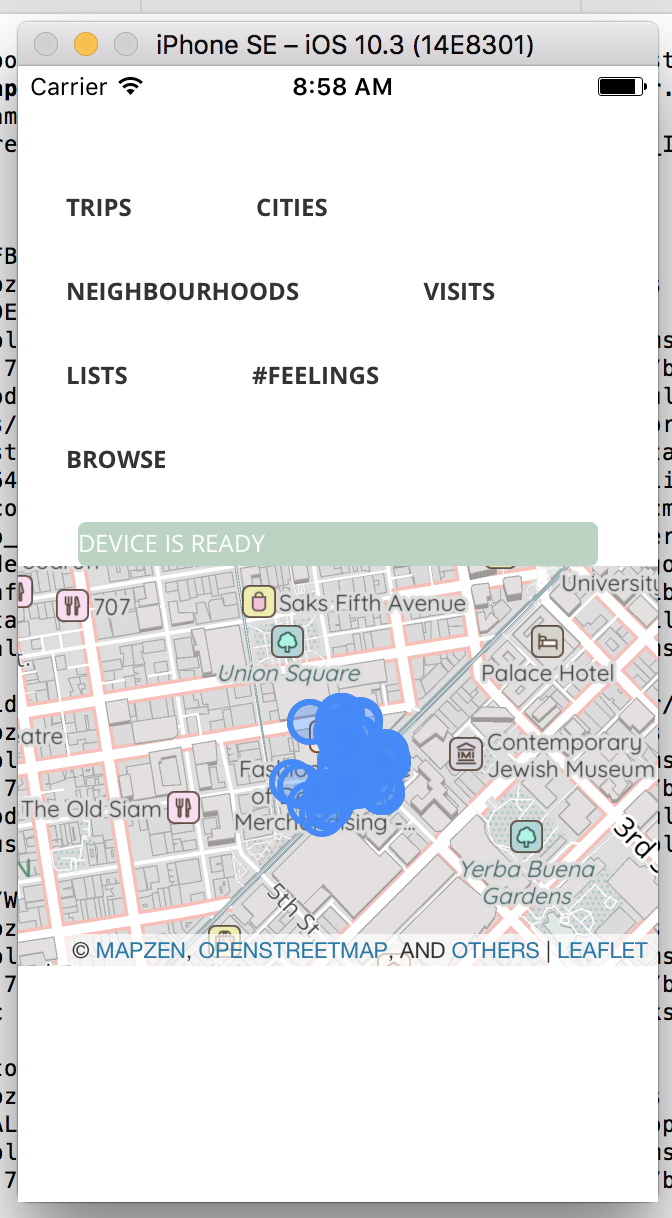

“Privatezen”, the application, is organized around six categories: Visits, Neighbourhoods, Cities, Lists, #feelings and Trips. All of these categories hold hands with each other meaning you should be able to look for all the visits in a particular neighbourhood or all of the lists that have visits in a particular city or #feelings associated with trips and so on.

”#feelings” used to be “desires” (as in Privatesquare’s Atlas of Desire) but a hashtag felt more in keeping with the times…

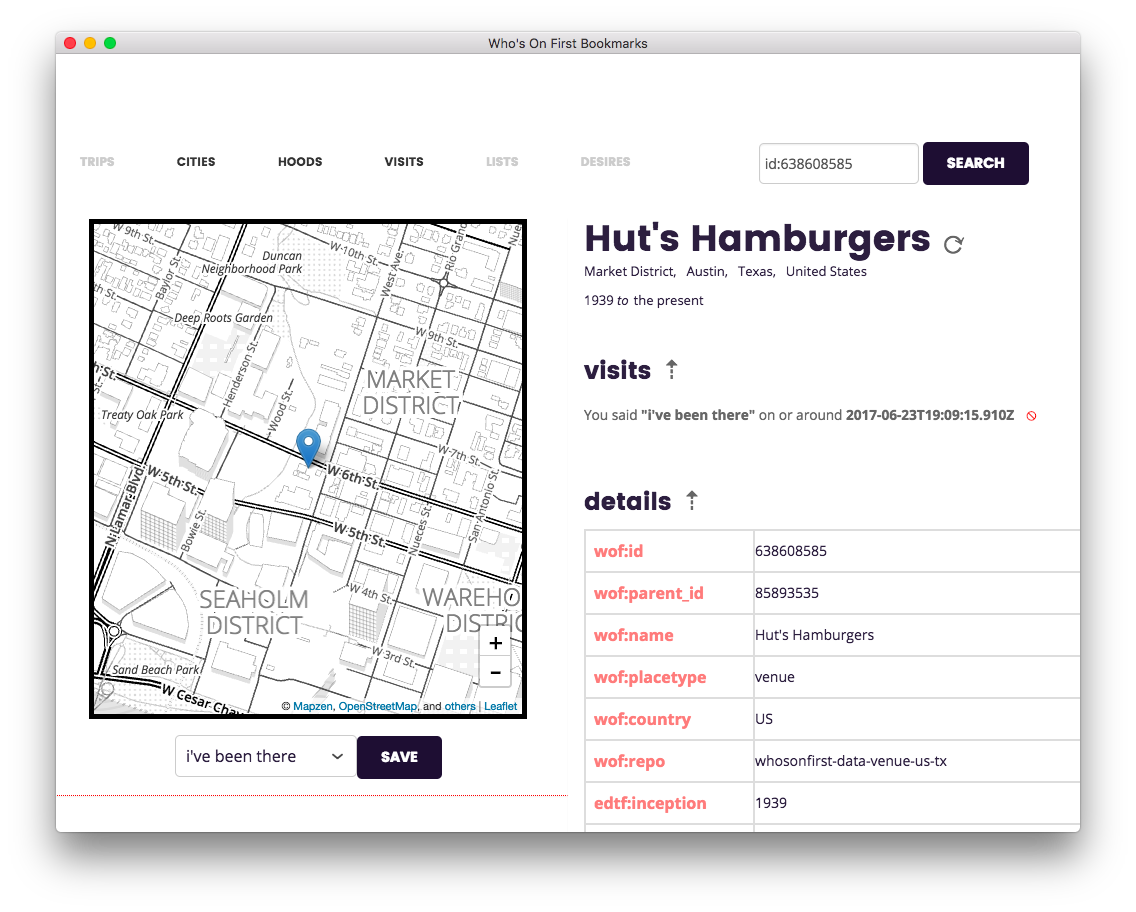

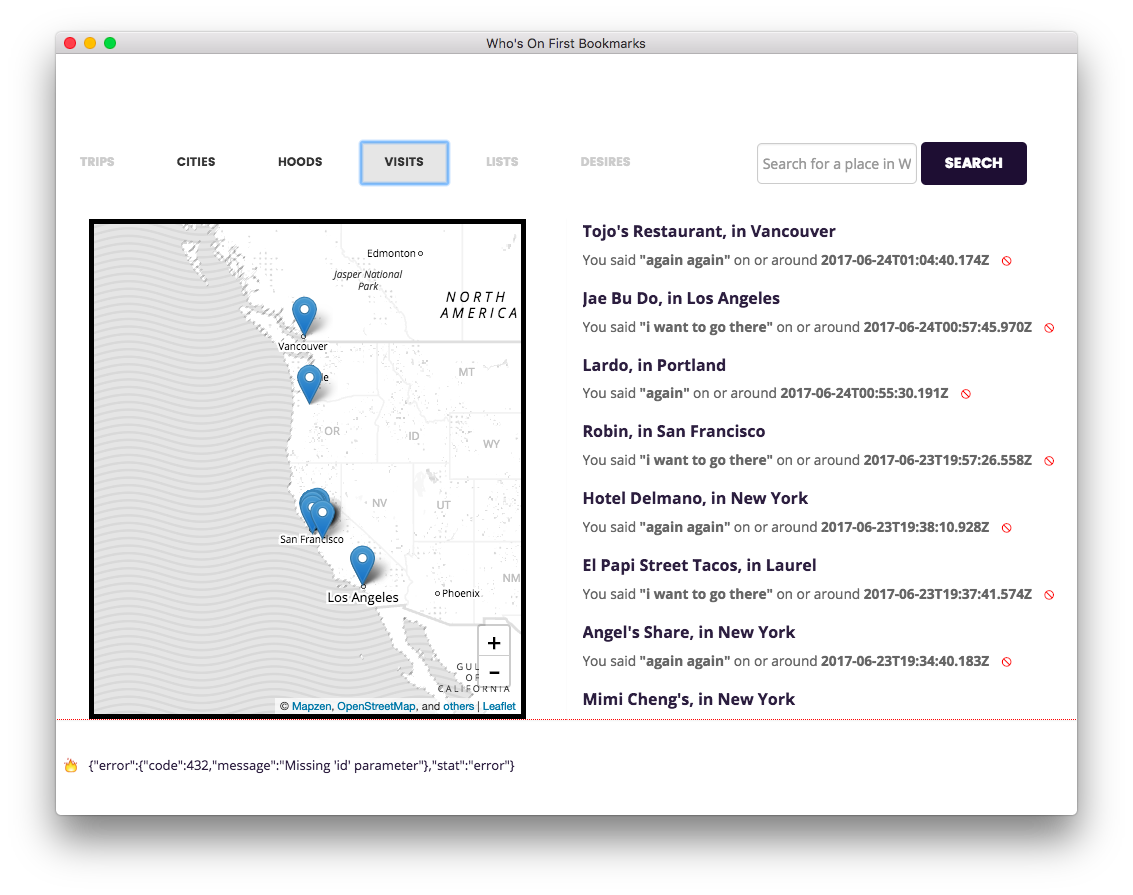

Here’s what a “visit” looks like:

Chief among the long list of short-cuts and gotchas is the fact that search has never worked very well, for three reasons.

First lots of venues (in Who’s On First) hadn’t been indexed in Mapzen Search yet. Second, we were using the mapzen.js library for map display and the Pelias API for search. Although the Who’s On First API implemented a Pelias-API compliant endpoint it was always buggy and those fixes just never made it to the top of the stack. Third, I just never got around to implementing a good generic list view interface for things like search results.

Instead, because I was the only person ever using this tool, I suffered the

hassle of looking up a venue ID (usually from the Spelunker) and

then, using the special syntax id:{WHOSONFIRST_ID}, would paste it to the search

box on the top right.

From there the application would look up the venue details and display them with a handy map at which point you could save your “visit” by saying nothing more specific than “I’ve been there” and the UI would update itself accordingly.

There are couple things to note: There was nothing venue specific about this interface. You could have saved any place in Who’s On First. There was also nothing specific about signaling when a visit took place.

const feelings = {

0: "i've been there",

1: "i was there",

2: "i want to go there",

3: "again again",

4: "again",

5: "again maybe",

6: "again never",

7: "meh",

8: "i would try this",

};

Although there is a timestamp indicating when a visit was added to the database the application doesn’t assume that you are recording things in the moment. In fact you can use the application to signal places that you want to visit.

I was also trying to integrate as many of the various Mapzen services, not so much for the sake of it but because they were all useful and to understand how they fit together and where the stress points remained.

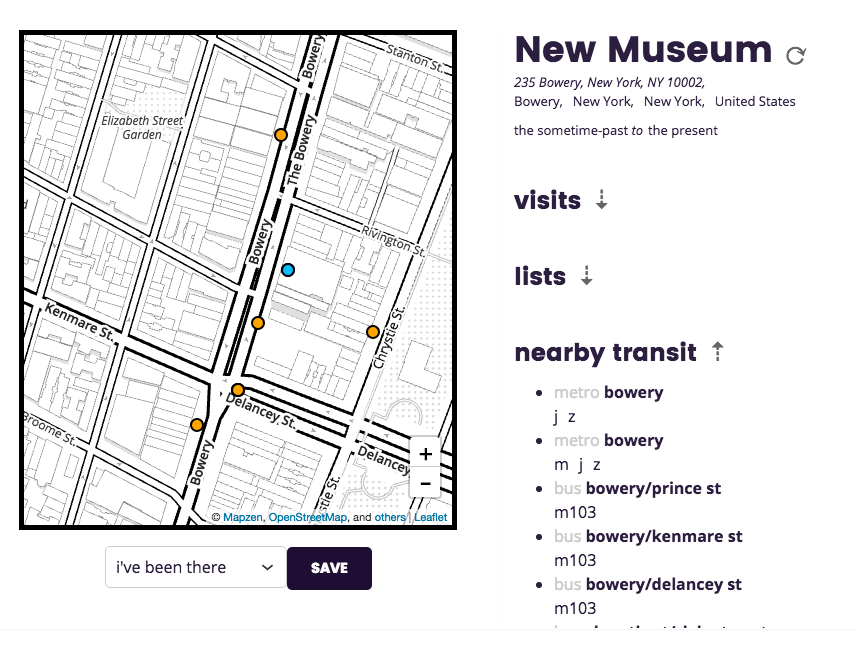

Once a Who’s On First place was loaded on to the map we would call the Transitland API for nearby transit stops. Like a lot of features this never moved beyond the basic prove-it-works-with-a-list-view stage on to a more refined and useful user interface.

Routing, and something like Dan’s All of the Places experiments from 2016, were also on the list but there was never enough time for all of the things…

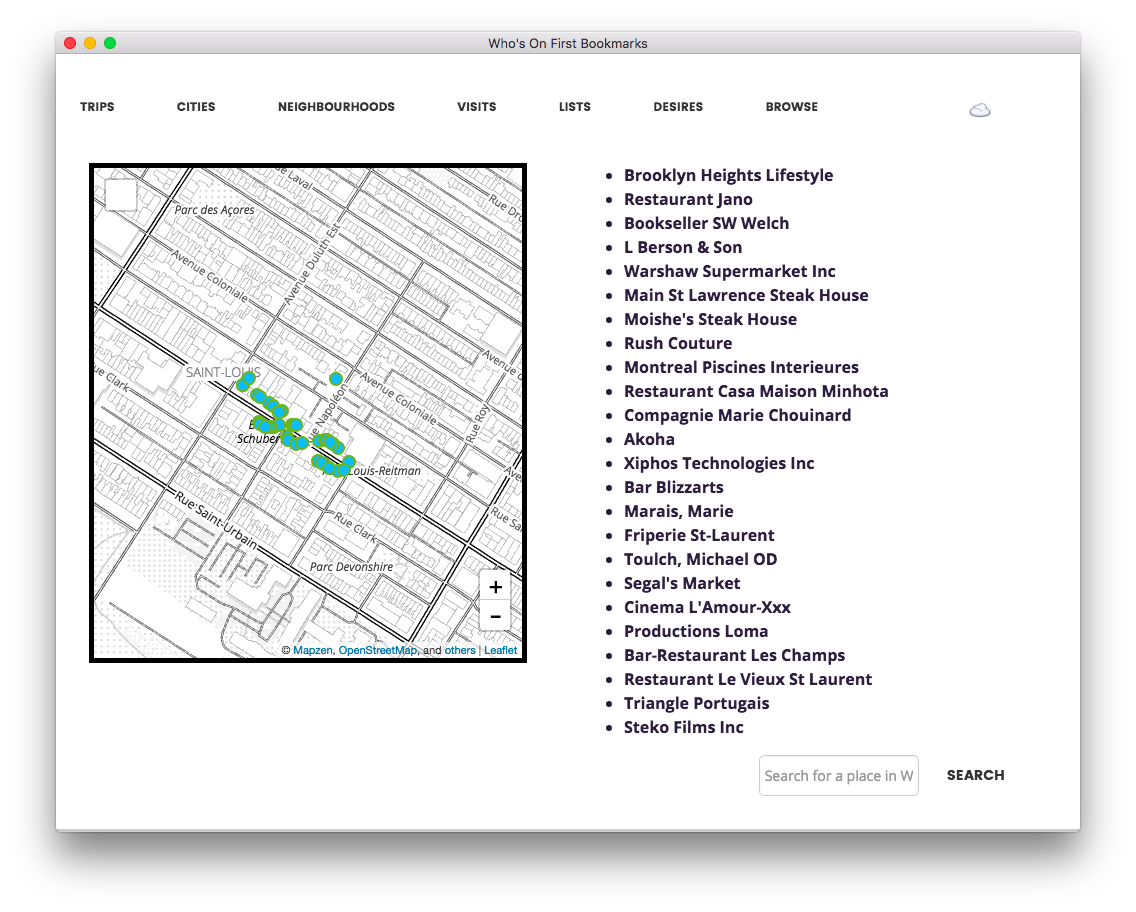

The default view when you launch the application is to show your most recent visits in reverse chronological order with a handy map. Generally the rule of thumb was to add “a handy map” whenever possible.

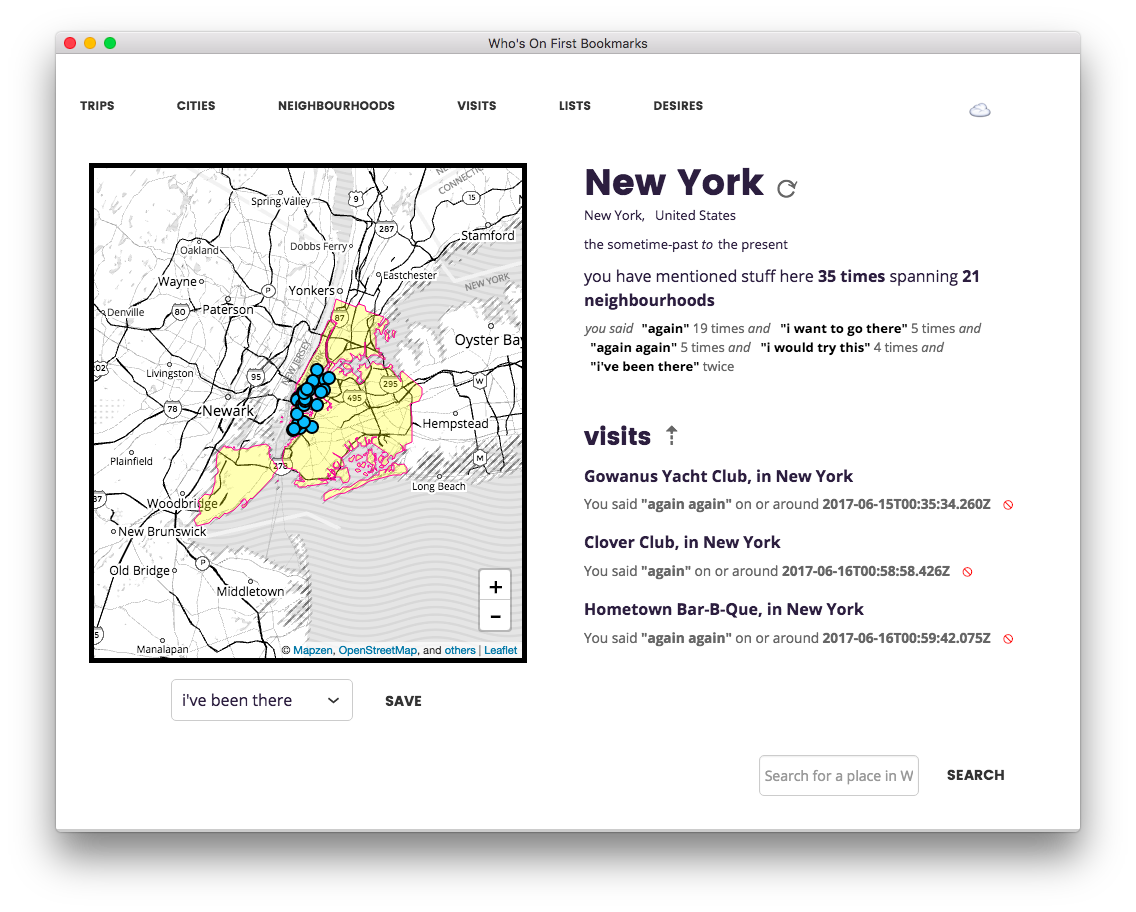

The other rule was to make every “first class object” in every view clickable. Here’s what I would see when I clicked New York City.

As you can see from the many dots on the map and only three visible “visits”, on the right, another of the many neglected UI details included how best to fit everything in to a finite amount of space and signaling when a given element overflowed the viewport.

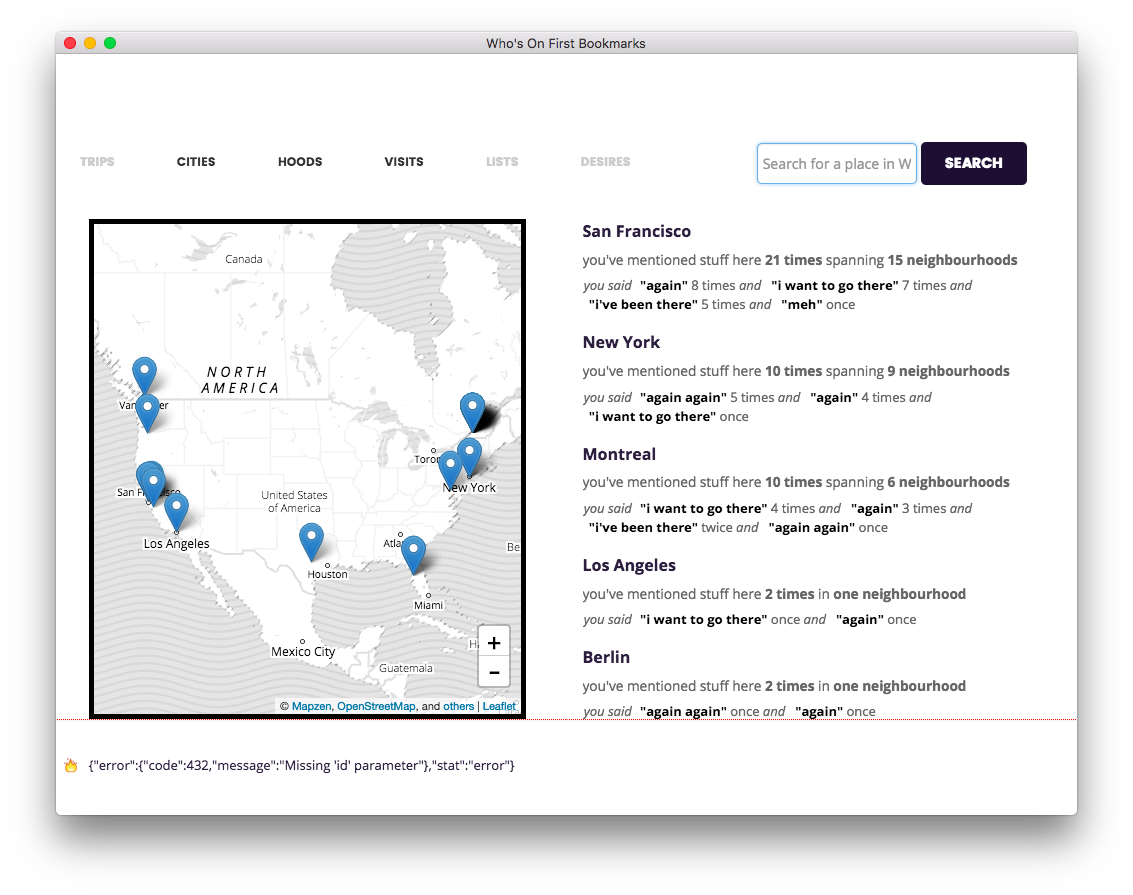

Here are the top cities that I had recorded visits for. These were grouped again by #feelings about the places that I had visited in that city. There are likewise views for neighbourhoods which was often very useful when trying to figure out where to meet someone for dinner and then immediately drawing a complete blank when asked to pick a spot.

Credit for the basic model of grouping things in to buckets labeled “again”, “again again”, “again maybe” and “again never” goes to Chris Heathcote.

It is possible to create lists and like the transit work, above, they never matured much beyond the “prove it’s possible with a list of items” stage.

You can add trips to places which is useful when combined with the “I want to go there” #feeling.

This is a straight clone of the trips functionality in Privatesquare which cloned the idea from the old social-travel website called Dopplr.

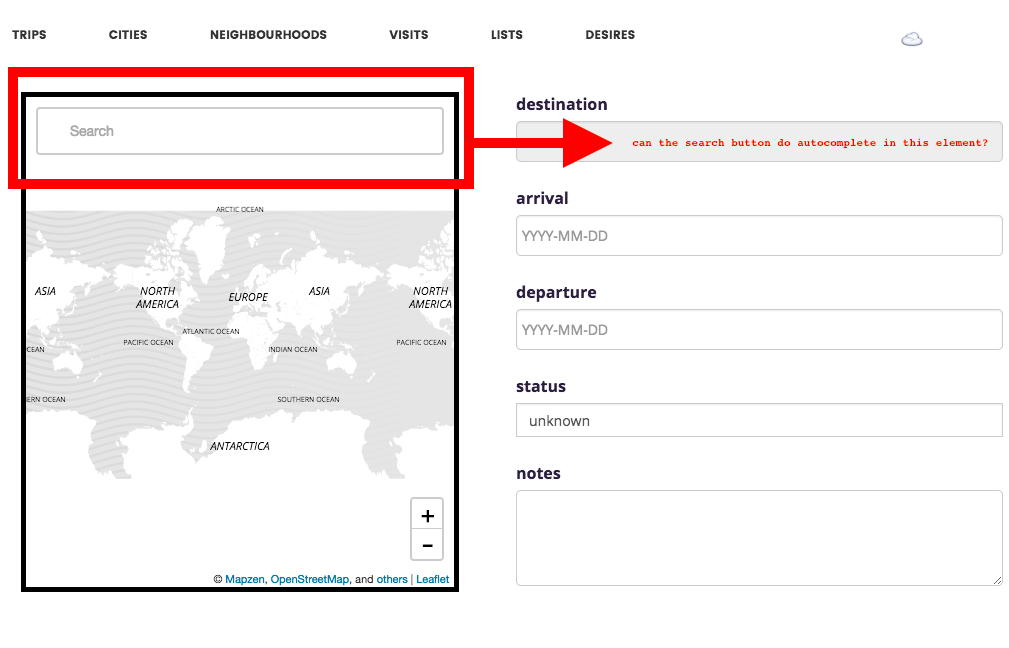

I never did figure out how to assign the mapzen.js search and geocoding widget

to another element outside of the map…

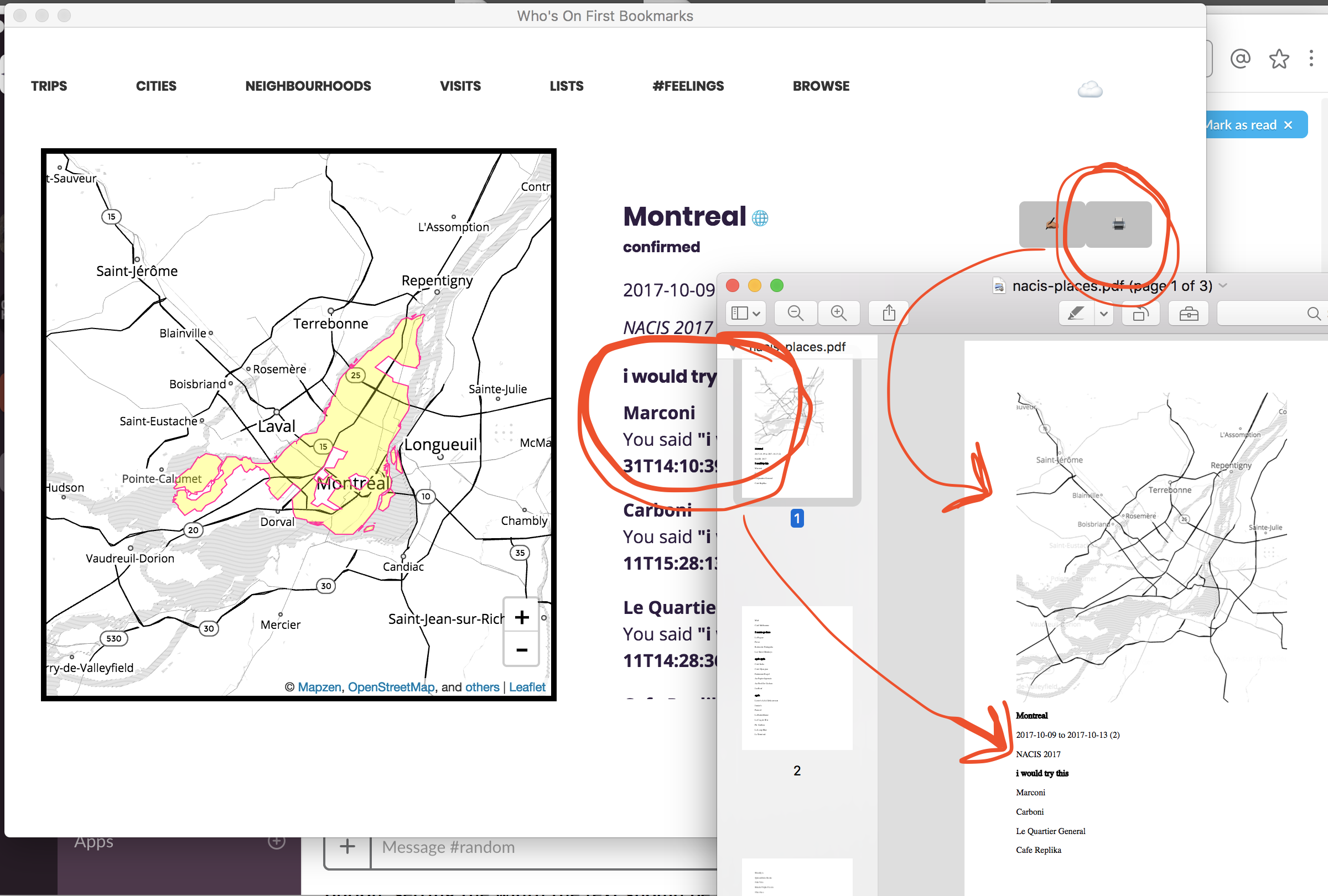

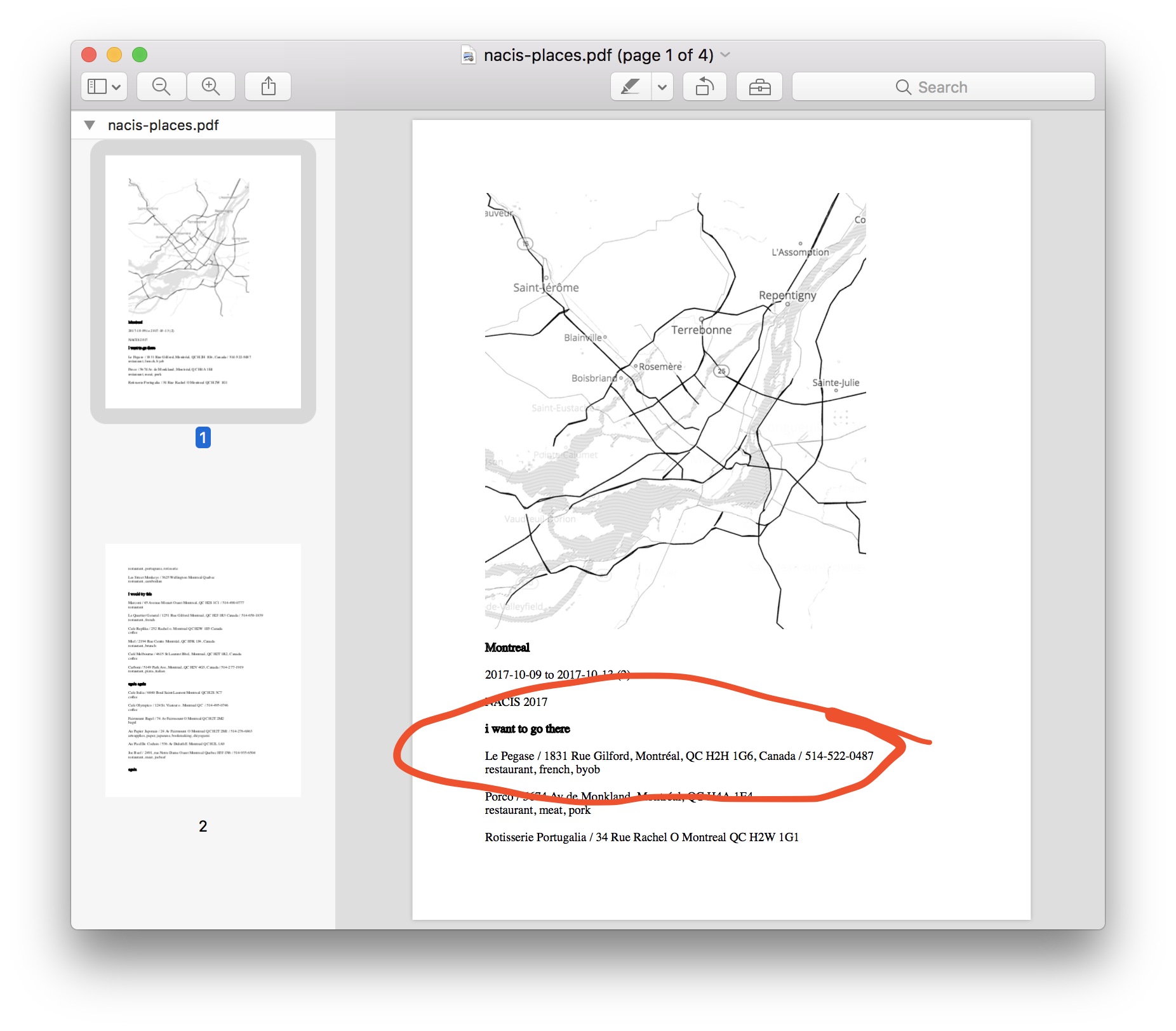

Before going to NACIS last year I spent a little bit of time writing the code to generate a PDF file of all the places associated with a trip, with an eye towards extending the functionality to any list view.

This work got stuck between the part where we use the Leaflet GeoJSON plugin to draw features on the map and the built-in ability of tangram.js to screenshot an image of the current map to include in the PDF file.

The problem being that because the features displayed on the map are being drawn

by a completely different map “layer” managed by

Leaflet that the tangram.js code doesn’t even know

about, from tangram.js ’s perspective there are no features to draw in screenshot-mode.

I mentioned earlier that there’s never been a proper interface for list views. Browsing all the nearby venues surrounding a point is a good example of that.

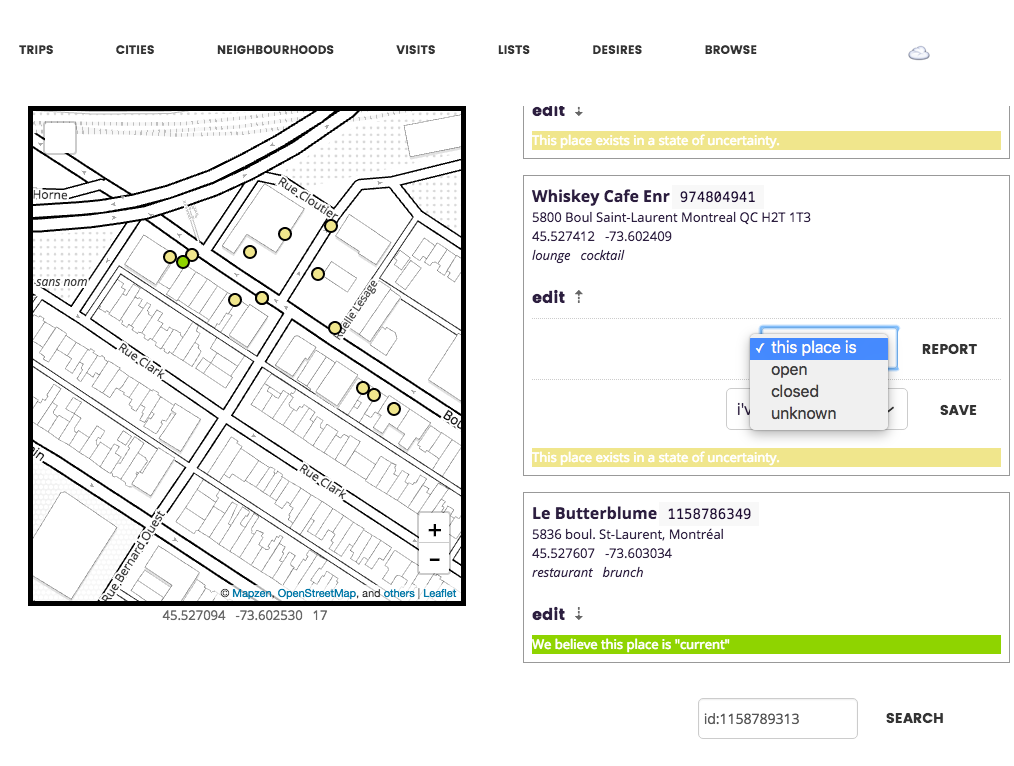

Here’s a screenshot of some work that I started to to do to develop a generic view (or “card”) for any given place. This included developing a range of colour-codings to apply to things like dots on the map, to signal properties about a venue like whether it was open or closed.

I always imagined that these views, or cards, could do double-duty as a place where people could help improve the underlying Who’s On First data.

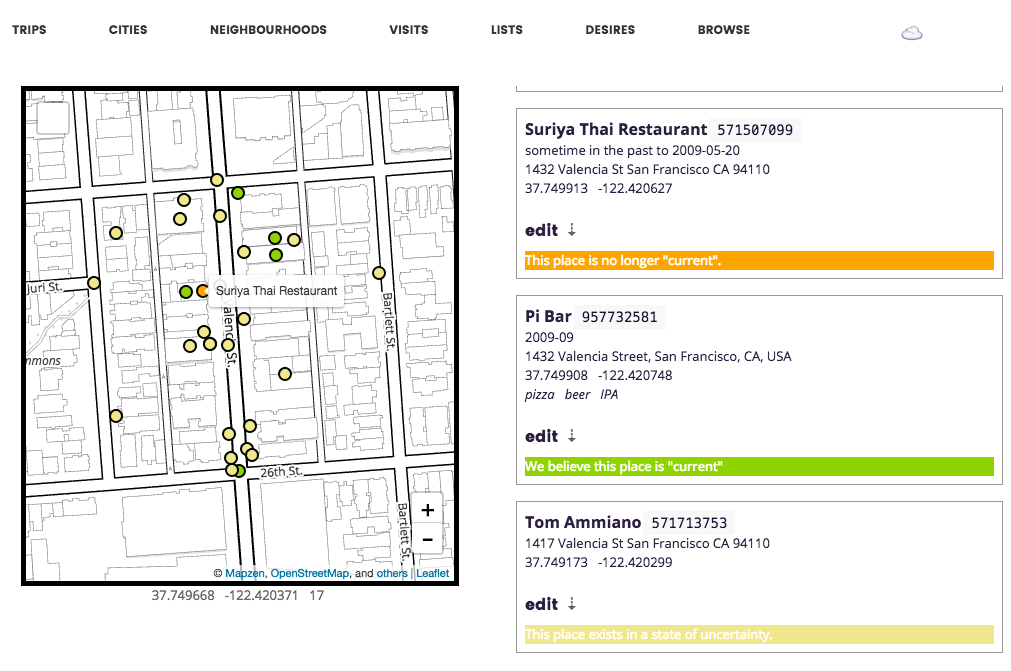

Here’s a tangible illustration of the the Who’s On First supersedes

and superseded_by properties in action. These two restaurants “occupy” the same

building: First Suriya Thai until early-2009 and then Pi Bar following that.

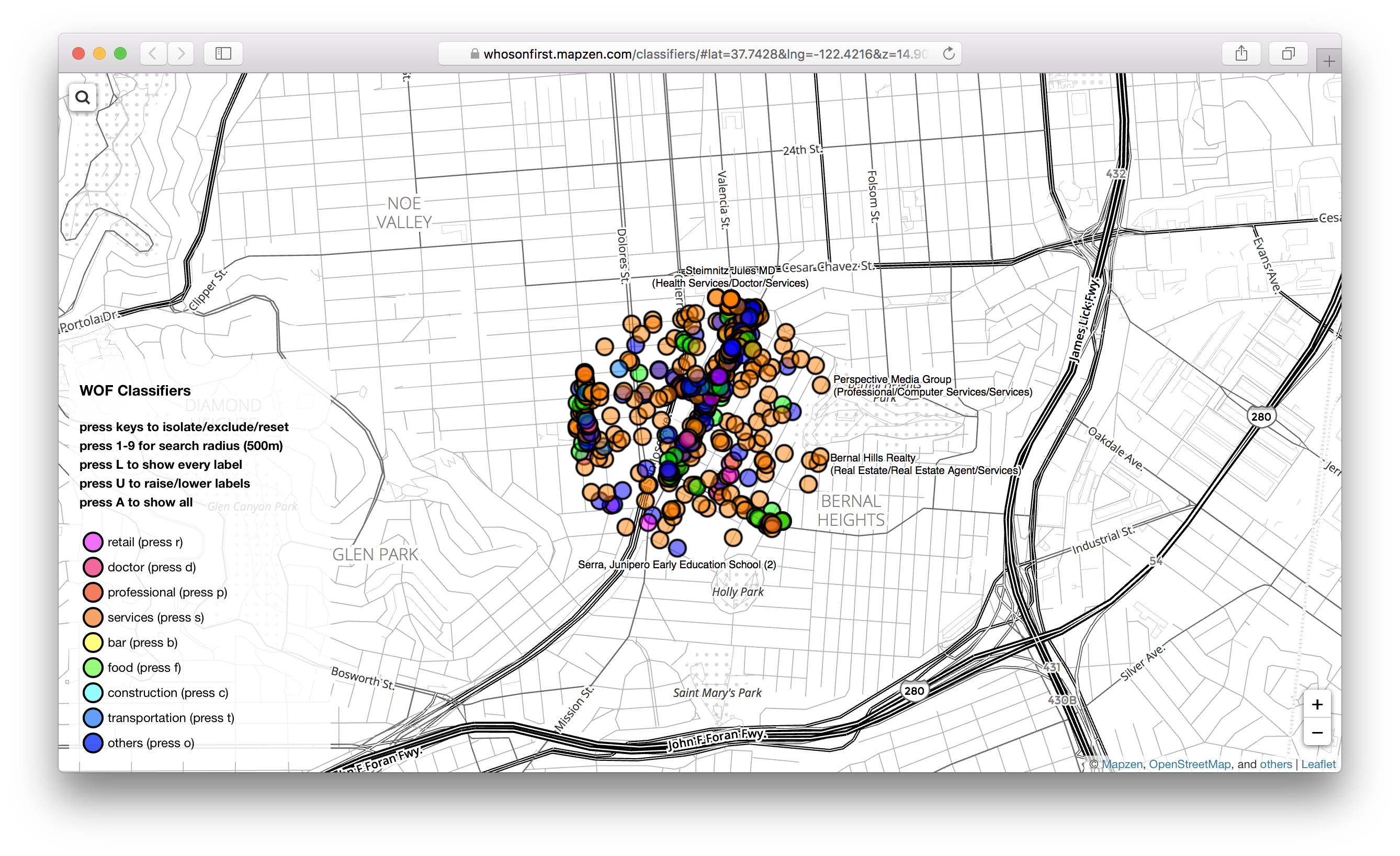

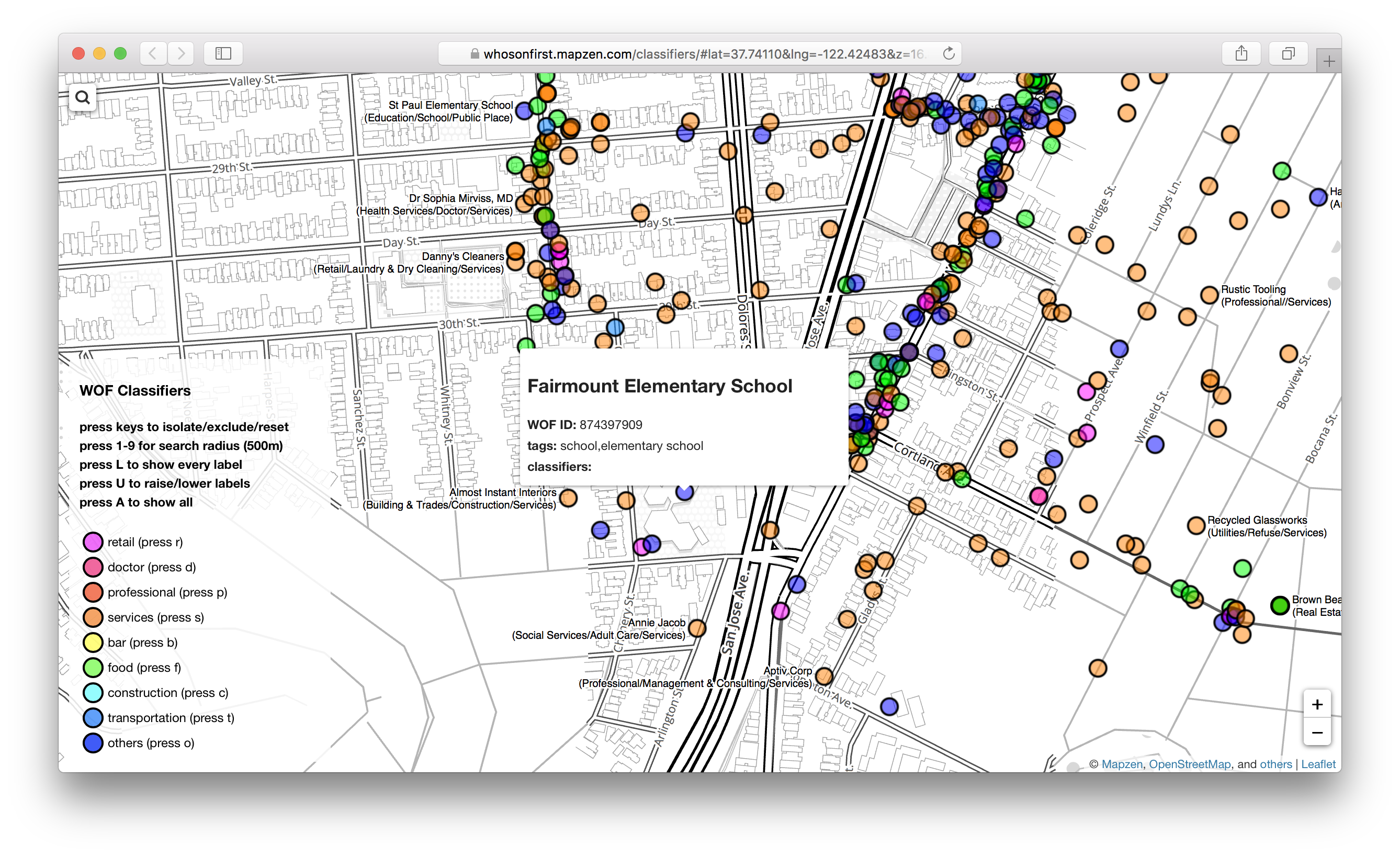

Speaking of colour coding dots on a map here’s a screenshot of some lovely work that John Oram did to display and filter venues by category.

This isn’t work that’s part of “Privatezen” today but there a bunch of useful tricks that could be applied from John’s work.

If nothing else John is drawing all

those dots in tangram.js rather than using the Leaflet GeoJSON plugin which

means if we did the same in “Privatezen” then we wouldn’t have the

dotless-screenshots-for-use-in-PDF-files problems described above.

We’ll badger John in to writing a blog post about his work soon.

The application does a few other things that aren’t as easy to screenshot, or even if they were make for really boring screenshots. For example, “Privatezen” is designed to work offline.

It works offline in the sense that because the SQLite database is sitting on your computer you don’t need to fetch everything from a remote server so pretty much everything except search and maps (discussed below) will work as expected, regardless of your internet connection.

It sort of works offline in that the application will keep a local cache of

Mapzen tiles that it’s used to display maps and once a map has loaded for a

specific place (a neighbourhood, a venue, etc.) then it will ask tangram.js to

take a screenshot of the map and store it on disk.

The next time you visit that place in the application the first that will happen is the the screenshot will be loaded underneath the map. If you’re online or if you have cached map tiles the screenshot will be covered up but if not you still have a visual representation of the place you’re “looking” at.

It doesn’t work offline when it comes to adding new things. As mentioned search doesn’t work but even if you happen to know the Who’s On First ID of the place you’re trying to add the application needs to fetch the details for that place over the wire.

Now that we’ve started building bundled SQLite databases of Who’s On First data I can imagine a scenario where you download one or more “bundles” specific to your interests, say just the venues in one or two cities, and those are used for lookups if the API isn’t available.

The other notable place where “Privatezen” doesn’t work is adding new venues that don’t already exist in Who’s On First.

I 100% agree with everyone who thinks it would be really useful for people to have a mechanism that allows them to create new places in the application, even if they’re only stored locally.

You might even think that should have been the first thing I worked and maybe I should have. This is the part where I look at my shoes and mutter something about “mornings and weekends”…

I think I punted on it because it starts to get complicated pretty quickly between having to generate and store local IDs and then to reconcile them with Who’s On First IDs, not to mention the lack of an API or even a simple way to submit a pull request against the data stored in GitHub.

These are all things that need to be done but here’s me looking at my shoes and muttering something about “mornings and weekends”…

Nor are there any “clients” beyond the desktop application. All the fancy talk about encrypting and decrypting SQLite databases over the network is just fancy talk at the moment. There are the beginnings of a Cordova-based application to do just that but so far it’s mostly just been a reminder of why programming native/non-web applications is… challenging.

As mentioned the desktop application is an Electron application so it’s all written in JavaScript and CSS and a tiny amount of HTML. It’s mostly a lot of boilerplate JavaScript.

I think you’re supposed to use something fancy like React to build applications like this, these days, and if I had to do this sort of thing 40-hours a week I probably would have invented something like React too. Instead it’s just a lot of JavaScript libraries that load and call one another and, aside from the part where “Privatezen” works, I am willing to accept that I’m “doing it wrong”.

At one point, building “Privatezen” became an exercise in trying to refactor or write all of the Who’s On First Javascript libraries to work in both a browser context and a nodejs context. They don’t yet, or at least not all of them, and I doubt any of them do it well. But that is the goal.

I’ve been referring to the project as “Privatezen” in this blog post but the actual code is stored in a repository with the very dull name of:

https://github.com/whosonfirst/electron-whosonfirst-bookmarks

There are build instructions for the applications (eventually there will OS-specific binary versions) but that’s about it as far as documentation goes right now. Honestly, this blog post will probably serve as the best piece of documentation about the project for the time being.

There is also the awkward reality of Mapzen itself shutting down along with all of the services the application uses, including the Who’s On First API. That was never part of the plan.

I actually don’t think it will be a big deal between the Nextzen tile release and Mapzen Search blossoming into geocode.earth and the Who’s On First API eventually re-surfacing (and I promise it will if only because I need it).

It might be nothing more complicated than swapping out endpoints and API keys for the different services and wouldn’t that be a nice way to dull the pain of Mapzen shutting down?

A few final words about #feelings.

At State of the Map US, last year, I told the story of the minor freak out I had during a meeting, early on at Mapzen, and asking people to accept that there were no open venue datasets for us to piggy back off of. The consequence of that fact is that a lot of our work would be trying to find new ways to have people contribute data, a lot of it data that many people had already gone to the trouble of adding to services like Foursquare.

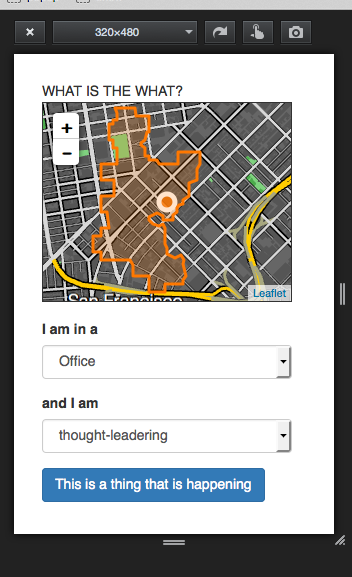

The gem that fell out of that meeting, for me, was an idea for a brain-dead simple mobile application that allowed people to talk about what kind of place you were in and what sort of thing you were doing, rather than a hyper-specific narrative.

What if instead of saying you were at a specific place with a specific address, which we didn’t know about and which you didn’t want to waste time pecking in to a mobile UI, you could just record that you were “at a bar” ? And what if the way to add meaning and nuance to that fact was to add a “feeling” to the signal.

For example, what if you could say “I’m at a bar, crying” or “I’m in a telco, hulking out”. The list goes on. Those two statements (category plus emotion) combined with a latitude and longitude, multiplied by a lot of people, start to fill in a lot of gaps.

It was meant to be something you could do in the moment, ideally with nothing more than your thumb and without making your friends feel like you were more interested in your phone than you were in them. It was meant to be something that could convey just enough information in the moment, with enough wiggle room for people to play with.

Ideally we would have wanted for people to go back and fill in the names and addresses for all the “bars” and “restaurants” where they were “drinking” and “crying” but even if they didn’t it would be enough signal for us to start working with and using to prioritize future-work.

{

"feels": [

{

"label": "being the decider",

"label_clean": "being-the-decider",

"id": 135726611

},

{

"label": "crying",

"label_clean": "crying",

"id": 102681251

},

{

"label": "drinking",

"label_clean": "drinking",

"id": 102681341

},

{

"label": "eating",

"label_clean": "eating",

"id": 135877017

},

{

"label":

"incentivizing",

"label_clean": "incentivizing",

"id": 135726609

},

... and so on...

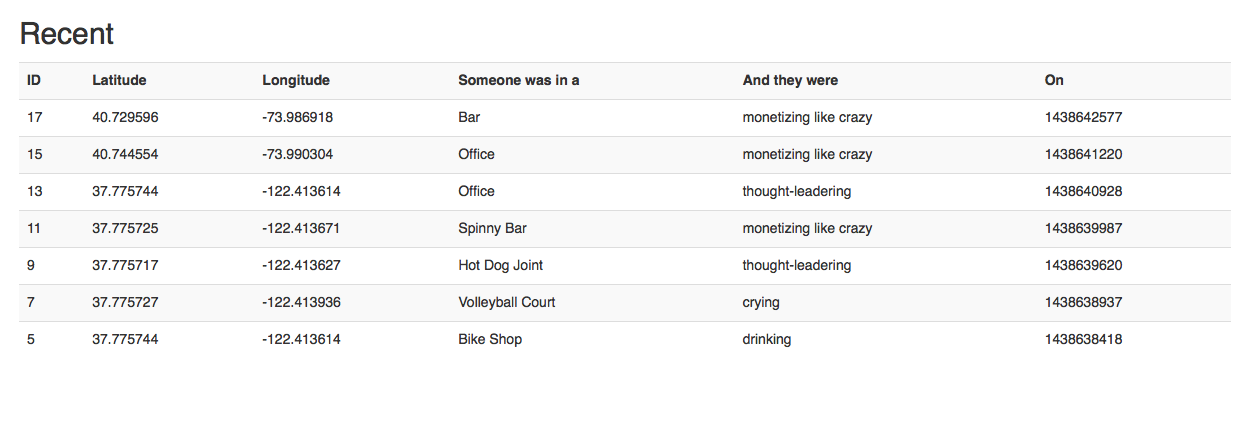

Sadly, it’s not a project that ever went anywhere. The database schema that I scribbled out on the whiteboard that afternoon sat there untouched for 18 months (maybe more) but point of telling this story is not to bemoan our inability to ship the simplest and dumbest of user-facing applications. Instead it is to celebrate the silliness, and the usefulness in the silliness, of the framing devices we imagined for what was little more than a “check-in” application.

On the surface recording a lot of people “crying, in bars” or “monetizing like crazy, in offices” doesn’t seem like it would be useful but I don’t buy that argument.

I remain convinced that if we’d be been able to devote a little more time than we had to polishing the rough edges off of this idea we could have not only made short work of the “no open data venues” problem but also had fun doing it at the same time. Fun, it turns out is… well, fun.

It’s something I try to remember while building “Privatezen” and why the application has #feelings.